Time as a KPI: The future for product success

Introduction

Remember the Jetsons or Pixar’s Wall-E? One displays a joyful free life; the other, a more dystopian view. Both, however, cover the same theme: a time where AI and robotics serve humans, and humans no longer have to work for sustenance.

Despite decades of technological advancements, the promise of a Jetsons-esque utopia remains elusive. In fact, studies consistently show that average working hours have barely budged. We have built tools for speed in productivity, but rarely for time for people.

I believe this is because of the fundamental ways we run businesses and measure success. Let’s evaluate where we are, how we operate, and what needs to change to create a better future.

The evolution of how we consume software

Not so long ago, software and applications we purchased had a single price tag, and success was simply measured by the volume sold.

When the time came for a new version to be released, it wasn’t the iterative process we have today. A new version might come out after a year or two, and success would be measured by two separate cohorts: first-time buyers purchasing the full license and returning buyers purchasing an upgrade at a discount.

As we moved toward web and cloud computing, expenses for businesses went up and subscription models became the norm. This model is very beneficial to the company, as profits month over month became predictable and regular updates could be made without users spending time downloading and installing new versions.

So which model is better? For businesses, the cloud and subscription model is naturally appealing—not just for revenue, but also for understanding user needs earlier. If users sign up and then cancel shortly after, the business can quickly investigate the issue. This is also beneficial for users, as they can try the software at a lower cost (or free trial) and cancel at any time if it doesn’t suit them.

With the older model, a user paid a large sum upfront to own the software. Even if the user never used it, the business had already achieved its revenue goals. While good for short-term financial targets, this created a long-term risk: users may choose not to upgrade or may stay on the original version, reducing future revenue.

Today, however, many installed software products are also tied to the cloud and depend on the company’s ongoing operations. They typically come with subscription pricing as well.

So why does all this matter?

In the early days, companies could afford to be relaxed about feedback—once licenses were sold, revenue goals were met. Now, cloud computing brings new pressure: keeping users onboard and active.

This fear of churn becomes the engine behind today’s KPIs: retention, engagement, and deeper integration into customer workflows.

However, I believe user behavior is shifting. If companies fail to recognize this change, newer products with more modern thinking will eventually surpass them.

Are we really user-centric?

Many companies claim to be user-centric. They talk to customers, map the user journey, review customer touchpoints, conduct usability testing, analyze data, send surveys, and plan the product roadmap based on customer needs.

But in this entire process, where is the user? We ask what challenges they face within our product space and pounce on any opportunity we find.

But that opportunity is only half the story. People and their challenges do not exist in isolation, and our solutions should not be built that way. We may solve a problem, but we also add another tool to the user’s workflow. We may save them time in one area, but we also change how they work with the people and environment around them.

Over time, businesses must grow. The natural path is adding features—features that require users to spend more time. We obsess over data and engagement, but what if users started evaluating products the same way?

Let’s imagine a user getting paid $20/hour. If they spend an average of two hours a day in your product, that’s still a cost of $280 per week—or $1,120 per month—plus your subscription fee. Are there better options? Maybe not yet. But if users begin thinking more granularly, that $1,120 per month (or $13,440 per year) becomes meaningful.

This shift is already happening. People are tired of the notifications and constant app demands. After nearly two decades of being pulled in by alerts and engagement cycles, users have had enough.

So which KPIs should define success—retention, engagement, the amount of data users input to remain locked into the ecosystem? Most products optimize for business-first goals. But in the era of AI and automation, it’s time we adopt a new measurement of success.

Time as a success metric

The acceleration driven by AI models and agents is not just increasing speed; it is increasing the noise we must navigate daily. The market is crowded with products and software, and the only way to win is to become a signal of relief.

As mentioned earlier, many products gather tremendous amounts of user data—from the projects they’re working on, to their calendars and availability. If we’re collecting that much information, at minimum we should be using it to reduce digital noise and improve balance in the user’s life.

Focusing on context

We need to understand where, when, and why users interact with the product. Who is with them? Who is around? What triggers usage? Is it collaborative? Does it involve observers? What about the timing and volume of notifications?

All of this matters when creating the next generation of human-centered experiences.

For example, in certain industries, data may reveal that users who interact with a product in the morning are more productive and spend less time switching between tools. Optimizing the product to reduce total time spent could be a major win.

Notifications are another area. Are users commuting? Is this normally when they open the app? Similar to how calendar alerts are sent at useful moments, perhaps push notifications should only arrive when the user is most likely to act. Just as people don’t want telemarketers calling during dinner, they don’t want non-urgent alerts at the wrong moment. And realistically, most products are not emergencies.

The ability to change culture

Remember Facebook—or any social platform? It started with good intentions: bring people together and share life with loved ones. But companies eventually require engagement to be profitable.

So they built notifications, tuned algorithms, and optimized experiences that kept people hooked. A platform built to connect ultimately drove many users apart. This happened because the platform did not account for the people and environment around its users. It is an extreme case, but many products risk the same pattern in smaller ways.

Whether in social media or workplace software, every time a product drives usage without considering the user’s environment, it risks disconnecting them from the real-world community around them.

As we build products and features, we must understand the full picture—including the real-world cost of usage. Individually these costs may seem small, but compounded across multiple products and add-ons, they become meaningful and difficult to undo.

Time as KPI

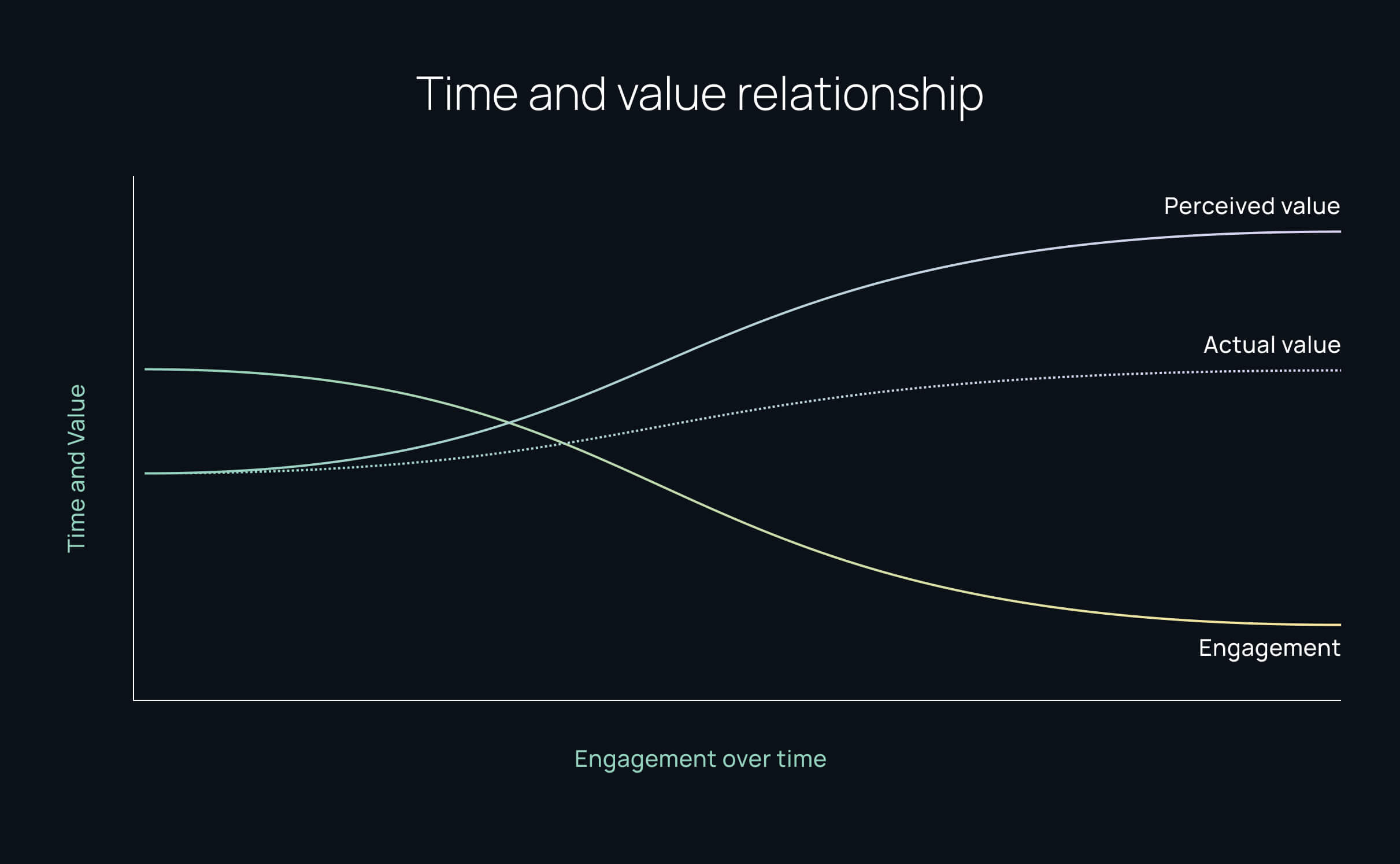

This is the natural evolution of customer-centric design: a success metric where we aim to reduce the time users spend in the product while increasing the value delivered.

This is not as counter-intuitive as it sounds. But if we sit and think about it, if the value delivered to a user remains fairly constant, but the time in the application decreases, the perceived value of the product will actually increase. This concept represents a new definition of a Minimal Lovable Product (MLP)—a product that is minimally present in a user’s life while delivering high value.

That utopian vision we dream of? This is a practical step toward it. Users still rely on the product, but time-consuming interactions are minimized, simplified, or automated so that users gain equal or greater value with less investment.

Imagine a competitor announcing:

“Our commitment to Time as a KPI has reduced average user time in product from 2 hours to 30 minutes per day, saving customers thousands of hours this quarter.”

This is the kind of metric that builds trust, strengthens retention, and reshapes market expectations. It does not live in isolation, the challenge is bringing this new KPI in and seeing how it supports the KPI's that already exist.

It is not a pipe dream; it simply requires a shift in mindset and priorities.