At the crossroads of Hicks law, ethical design, and AI interfaces

AI has taken the world by storm over the last few years. With it has come a flood of possibilities, and a new set of challenges. The hot topics up for discussion is anything from privacy to data usage; but I want to touch on a different topic. The paradox of choice and how this may actually create concern from a business and ethics perspective.

When it comes to AI assistants and language models like ChatGPT, the design choice to use a single freeform textbox feels fitting. Users can input anything that comes to mind, because, well, it’s meant to be an all-in-one assistant. It is capable of doing everything up to a certain point, but when it comes to detailed and very refined or niche requests, the results are lackluster, at best. It’s like a jack of all trades, master of none.

But the generalist AI models are not necessarily the target of my discussion. AI services built for specialized purposes need to take into consideration an important principle in the design world: Hick’s law.

The psychology of choice

Hick’s law states that with the more choices we have, the longer time we take to decide what we want.

A great example of less is more is the popular burger chain “In n Out” in the United States. Their menu is simplified to just a hamburger, a cheeseburger, and a double-double. The only other choice you need to make is if you want a drink and fries. That’s it.

Research supports this mode. A recent study shows that higher conversion rate comes with less offerings.When presented with choices of jam, only 3% of customers made a purchase when given 24 flavors of jam, whereas 30% made a purchase when only given 6 flavors to choose from.

Now imagine walking into a restaurant that has a book of menu items. Overwhelming? Sure. But let’s make it even more challenging. This restaurant has the same book of items, but the menu is to be discovered by asking the waiter your requests. They may or may not be able to do it; or perhaps they will try, but the food may not be as expected.

You might spend a few exchanges with the waiter just figuring out what you can order. Eventually, you settle on something. But then, you see the table next to you receive a dish you didn’t know existed, or how they ordered, and suddenly, you feel that subtle sting of FOMO. You’ve already paid, and it’s too late to change your order. Maybe next time.

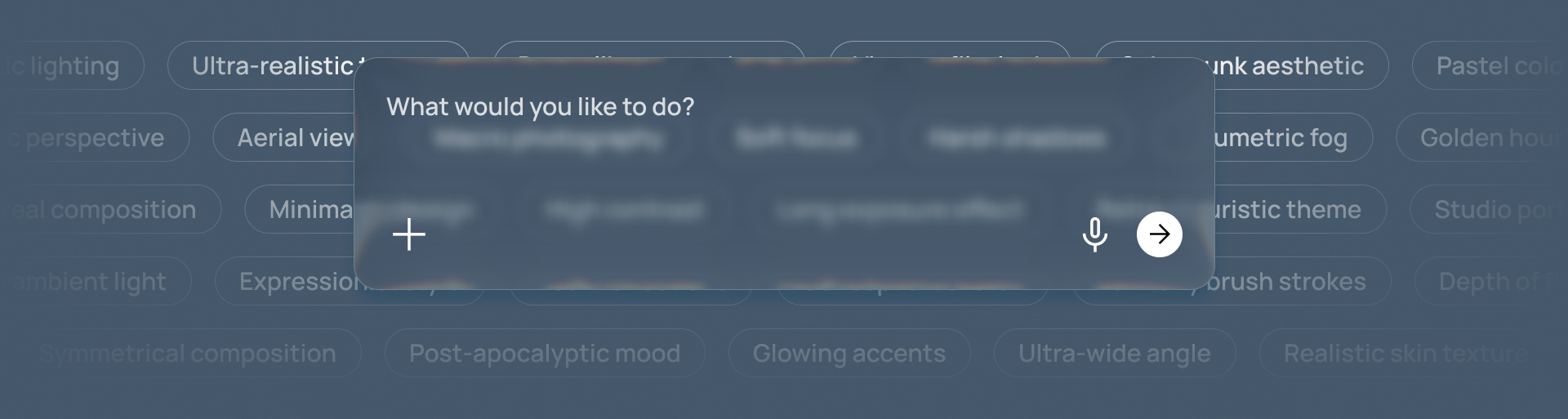

This is the type of experience we are building with open prompt AI interfaces: an unknown amount of possibilities with an invisible structure. The menu hasn’t disappeared — it’s just hidden behind imagination and what you can think of.

Many services now allow people who make requests to keep their prompt revealed for others to copy. This, however, doesn’t reveal everything and all the techniques possible.

The cost of exploration

When users pay for tokens to generate AI outputs, they’re not just paying for results, they’re paying to learn how to get results.

Each prompt in essence is a nanotransaction of uncertainty. Users buy a few tokens, type a few words, and hope for the results they expect. If not, try again. It’s gamified trial and error, and it can begin to feel a lot like gambling for results.

In any other context, this pay to play model would be absurd. Imagine every click and interaction in traditional software costing a few pennies. Yet in AI, this has become an expected norm.

Of course, there’s an economic reality to it. Running large AI models is expensive, and those costs need to be recovered. But that doesn’t absolve us, as designers and builders, from considering the experience and ethical concerns this creates.

Designing ethically and accessibly with open input

We often assume that freedom equals empowerment. But Hick’s Law reminds us that freedom without form becomes friction. The open prompt looks minimal, but cognitively, it’s one of the heaviest interfaces ever designed. It places the burden of creativity, accuracy, and exploration entirely on the user.

We have to ask ourselves what freedom really means in AI design. Maybe it isn’t about presenting an open window of possibilities, but about giving people just enough guidance to move forward with confidence. And if we want to take it a step further and talk about ethics, we have to make a brief mention about accessibility too.

Accessibility doesn’t just mean being able to use a product or interface—it means being able to use it effectively. If someone can technically access a tool but can’t navigate or get meaningful results from it, then we’ve failed to make it truly accessible.

If the open prompt remains the main interface, maybe the answer is to bring a bit of structure back. A simple questionnaire that asks what someone wants to create, what style they’re after, or what outcome they expect. The interface can then bring up best practices based on their goal, and turn ambiguity into clarity. It’s not about limiting creativity, it’s about giving the user guidance to success.

In short, we must start designing systems that help our users get better results before they pay for mediocre disappointment.

The challenge with AI continues however, when the creators of a service, especially in the writing and creative spectrum, how do we pass this knowledge to users when the creators themselves are trying to learn the power of their own models? This is an open question that I hope from a technology and user experience perspective, we can resolve sooner rather than later.